We all learn something about ourselves in difficult times. For some, the lesson is reassuring: Even in the worst-case scenario — whether it’s losing a job in hard economic times, mourning the death of a loved one, or coping with a debilitating illness — certain people manage to maintain their emotional balance. Instead of slipping into despair, they remain optimistic and focused enough to look for another job, cope with loss or illness, and generally keep going with their lives.

The ability to bounce back from disaster — psychologists call it “resilience” — is both highly valuable and a little mysterious. While it used to be considered a special trait enjoyed by only a few extraordinary people, recent investigations suggest that most of us carry at least the seeds of resilience. Researchers are working to figure out exactly where resilience comes from and how it can be relied upon when people need it most.

Secrets of resiliency

Resilient people feel distressed just like anyone else. But even in the darkest times, they manage to buoy their spirits with positive thoughts. “Even the most dire situations aren’t always completely one hundred percent bad,” says resilience researcher Barbara Fredrickson, professor of psychology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and author of Positivity (Crown, 2009), a book about the power of positive emotions. “The worst situations are often mixed with feelings of relief and an outpouring of compassion.”

The terrorist attacks of 2001, for example, gave the nation an unexpected lesson in resilience. As Fredrick and colleagues noted in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, many people managed to find positive emotions — such as affection for family members and a profound thankfulness to be alive — in the immediate aftermath of the attack. Such people also felt their fair share of fear and sadness, but they were less likely to slide into total despair.

Resilient people, it seems, can find solace even while dealing with overwhelming loss. As reported in the journal Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, studies have found that people who coped best with losing a spouse didn’t try to “make sense” of the death or spend a lot of time mulling over regrets or lost opportunities. Instead, while grieving, they found a measure of comfort in happy memories of their lost partner.

Resilience can even assert itself after torture and abuse. English researchers found that a large percentage of released political activists in Turkey were thriving despite having been tortured hundreds of times over the years. The torture survivors who showed the most resilience had a couple things in their favor: strong support from their families and their community, and a strong connection to their political cause. In some ways, the torture simply reinforced their belief that they were on the right side.

Positive emotions are more than just a short-term fix. Experts have found that feelings of love, gratitude, and relief can reverberate for years after a crisis. Why are these emotions so powerful and long-lasting? On a basic level, Fredrickson says, such feelings help keep the mind free and flexible. “You see the bigger picture. There’s a greater openness that allows you to connect with other people.” Now think about the alternative. As Fredrickson explains, people who are grief-stricken, anxious, or depressed tend to draw inward and limit their interactions with the world.

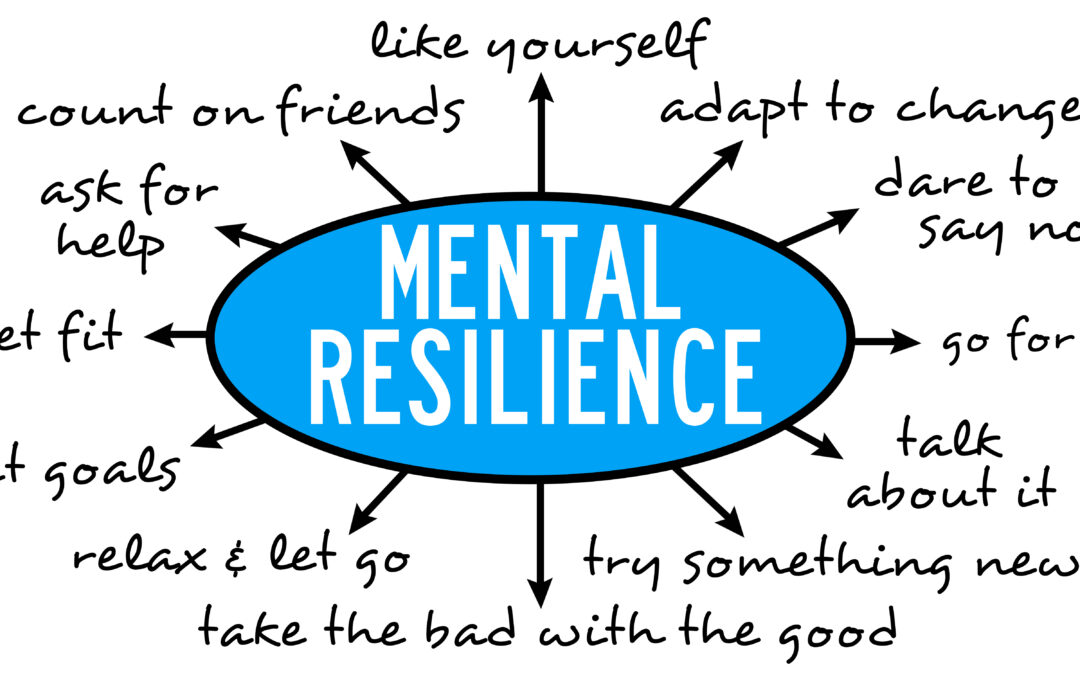

Although no one knows exactly why some people survive and even thrive after enduring severe loss and trauma, many experts agree that resilient people tend to share certain characteristics, which include showing good judgment, being thoughtful instead of impulsive, and caring about others’ feelings. They also tend to feel good about themselves, to have caring and supportive relationships outside their families, and to be skilled in communication and problem solving.

Building resilience in the face of disaster

Resilience seems to come naturally to some people, but others have to cultivate it, especially when disaster strikes. You may not be able to flip on an “optimism” switch, but you can take steps to help speed your return to normal. Writing in a 2003 issue of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, researchers at the University of California at Davis identified one extremely helpful strategy: Counting blessings. You can do that in your head, of course, but writing them down might be even better. The study found that writing down a list of things to be thankful for once a week for 10 weeks helped improve mood and well-being, even for people with neuromuscular diseases. In a similar vein, other studies have found that people recover from traumas better if they take time to write down any possible unexpected benefits associated with their situation — the job may be gone, for example, but that gives you a chance to find something better.

Florida psychologist Harry Mills, PhD and Ohio psychologist Mark Dombeck, PhD have other tips for building resilience. They recommend identifying a vexing problem that isn’t completely under your control. (By definition, you won’t be able to fix this situation with a wave of your hand.) Then try to find at least one way to make a positive change: Exercise a little more to help manage your diabetes, get a small concession at work. A better sense of control is a powerful buffer against stress.

Building optimism is another important — but sometimes difficult — step toward resiliency. Mills and Dombeck recommend trying to take a detached view of your situation. For example, pretend that you have a friend who is going through a situation identical to yours and imagine what you would say to him. There’s a good chance that your advice wouldn’t be so bleak. Instead, you’d try to help your friend see the encouraging side of both his present and the future. Turn that positive attitude inward, and you’ll be making some progress.

Resilient minds, healthy bodies

In difficult times, resilience can protect the body as well as the mind. In a major study published in the journal Health Psychology, Finnish researchers measured levels of optimism and pessimism levels of more than 5,000 people before a traumatic life-changing event. The people who were most optimistic before the tragedy (such as the death or severe illness of a close family member) seemed to be the healthiest afterwards. Specifically, they missed relatively few work days due to sickness.

Positive emotions and good humor — two hallmarks of resilience — can help strengthen the immune system and protect the heart. In the big picture, resilience can even help keep a person alive. As reported in the Journal of Personality, studies of men infected with HIV show that the most upbeat patients are the least likely to die prematurely, even after taking into account other factors (such as the severity of the infection and overall health). In a perhaps even more impressive feat of resilience in action, another study found that nuns who poured positive emotions into writings as early adults were especially likely to be alive 60 years later.

Practicing resilience

The benefits of resilience may sound great, but how do you make it work for you? “Forcing yourself to have a positive attitude isn’t helpful,” warns Fredrickson. Still, she says, it is possible to develop a mindset that gives positive emotions a chance to flow naturally. “The simplest approach is to practice being open-minded and appreciative of others. There’s human kindness all around us.”

The American Psychological Association offers additional tips to help you build your own resilience in good times and bad:

Make connections

Fostering strong, close relationships with family and friends can help you weather emotional storms. Stay involved with others through community groups or faith-based organizations.

Move toward your goals

Even if it’s only a minor step, do one thing today that will help you move forward.

Rely on yourself

Rather than criticizing yourself relentlessly, trust in your ability to solve problems.

Stay hopeful

The APA recommends that you visualize what you want, rather than worry about what you fear.

Take care of your body and mind

Engage in enjoyable, relaxing activities and get regular exercise. You’ll be stronger and better able to face the future.

Finally, recognize that nobody can be resilient all the time. It’s normal to feel stressed and overwhelmed in the face of crisis or tragedy. If you feel like it’s just too much to handle, seek professional help. Give your doctor a call, or talk to a trusted adviser or mental-health professional. Even the most resilient people need a hand once in a while.

Source: HealthDay: www.healthday.com; SupportLinc EAP